Sustainable & Resilient Monadnock Region

What if we plan to save a million dollars a year in energy costs?

Monadnock Sustainability Action Plan

In the Monadnock region, we spend around $350,000,000 every year on energy for buildings and transportation. Most of this money leaves the state to outside energy providers. Imagine if we could cut energy use by 30% through simple no to low cost strategies. We could reduce our energy bills and save a million dollars every year! It is in everyone’s best interest to reduce energy use and keep our energy dollars circulating locally.

The Monadnock Sustainability Action Plan is intended to reduce our dependence on imported fossil fuels and to improve the environment and human health in the region. This Plan resulted from a three-year citizen inclusive process and so reflects the priorities and concerns of local people as well as best practices in energy use and conservation. This regional climate and energy action plan is a practical guide for all sectors to identify and take actions to reduce energy demands.

In our rural region, collaboration and partnership between different sectors of a community, as well as among communities, are essential to the success of effective projects. This Plan is a product of such vital networking and lays out a community development vision founded upon people, institutions and communities working together for our common good.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1: Background Action Plan

Chapter 2: Community Consultation

Actions By Sector

Chapter 3: Municipal Sector Actions

Chapter 4: Residential Sector Actions

Chapter 5: Business Sector Actions

Chapter 6: Educational Sector Actions

Appendices

A: The Cool Monadnock Project

B: Sample Town Report

C: Case Study

D: Neighbors Helping Neighbors Gathering Participant Packet

E: Neighbors Helping Neighbors Results

F: Resources and Partners

Introduction

Introduction

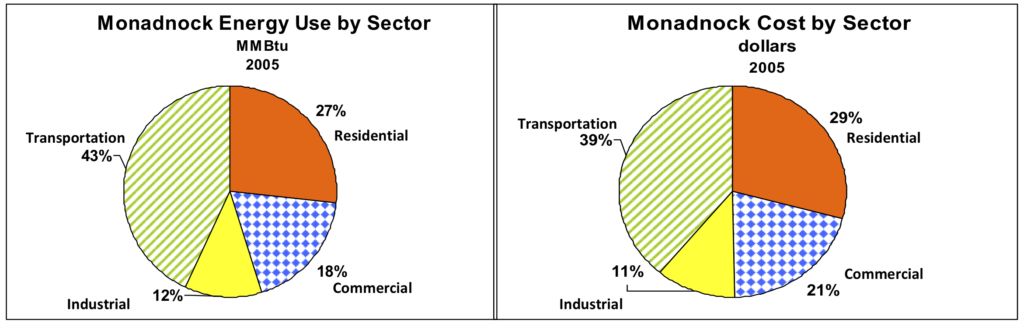

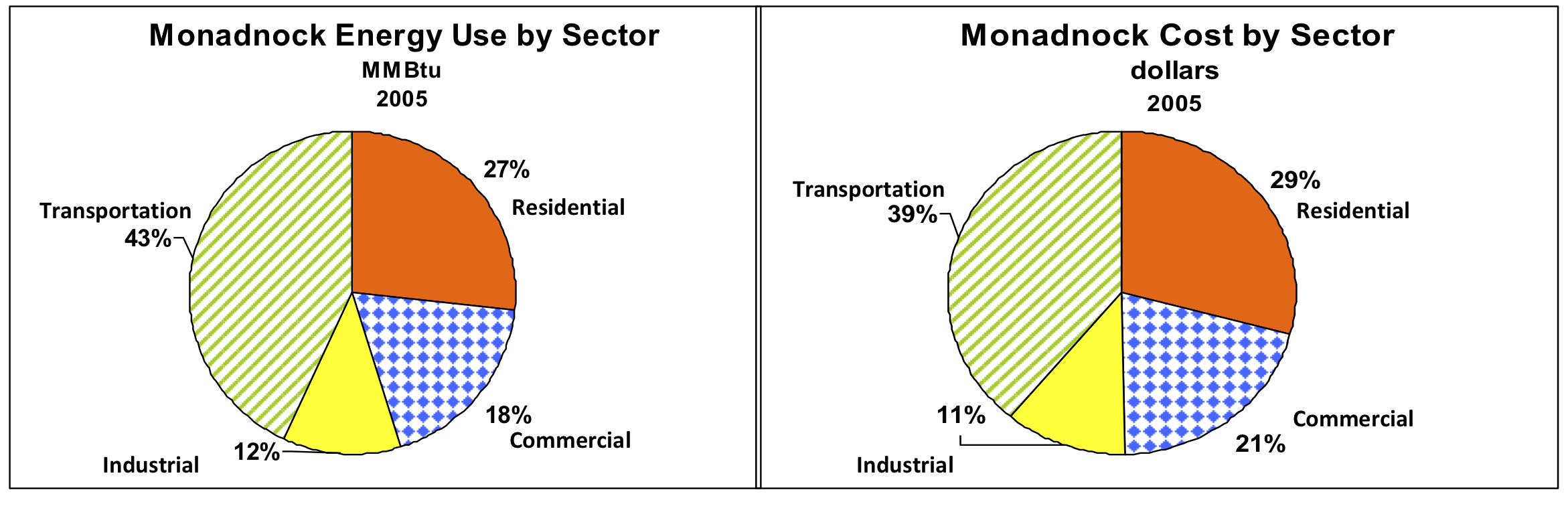

Based on a regional energy assessment, the Monadnock region spends approximately $350,000,000 on energy in our buildings and transportation needs. The graphs below illustrate the majority of our energy is used on the heating/cooling and electricity use of our buildings in the residential, commercial and industrial sectors.

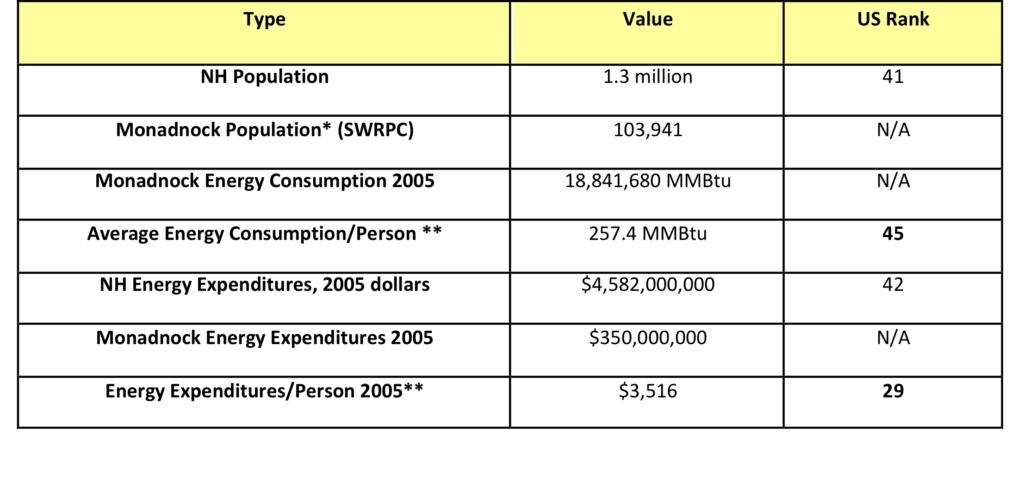

If we reduced our energy by 30% through simple no to low cost strategies, we could reduce our energy bills and save the region $105,000,000 a year. It is evident from the table below that while New Hampshire is ranked low for the amount of energy we are consuming, New Hampshire ranks a lot higher for the amount of costs we are spending on energy. This clearly indicates it is in every New Hampshire taxpayer’s interest and benefit to reduce our energy use and keep our energy dollars circulating in our local economies versus leaving the state.

* Population Based on 2005 OEP Estimate

* Population Based on 2005 OEP Estimate

** Based on NH Energy Facts 2005 data from OEP – represents NH state figure

The Monadnock Sustainability Action Plan has been developed as a basis to advance the work of municipalities, businesses, non-profits, institutions, and citizens in the Monadnock Region toward reducing dependence on imported fossil fuels for energy and improve the environment and human health in the region. This Plan was created out of the work of the Cool Monadnock project. It was developed through a three-year collaborative process. Due to this inclusive process, it reflects the priorities and concerns of local citizens as well as best practices in energy conservation planning. It is intended to serve as a point of departure for Local Energy Committees/Commissions, local planners, and municipal authorities, as well as concerned citizens and businesses, to chart a course toward energy independence and seek out resources and partners to further their energy conservation goals.

This regional climate and energy action plan is designed to serve as a practical guide for parties working on behalf of municipalities and local energy committees, residential groups (including civic organizations, faith communities, etc.), businesses and non-profit organizations, and educational institutions, as well as cross-sector groups, to easily identify and implement actions to reduce their energy demands. In a predominantly rural region, the importance of collaborative efforts between different sectors of a community, as well as among several communities, cannot be over-emphasized. The diverse voices consulted in the development of this plan advised repeatedly that creating these partnerships could provide a powerful foundation to increase the networks and knowledge base necessary for effective projects, to create markets of scale, and to demonstrate demand for particular local policies that enable these energy conservation projects.

Chapter 1 provides a succinct summary of the three-year work plan that culminated in the drafting of this plan. Chapter 2 describes the process of gathering public input into the plan. Chapters 3-6 contain the list of suggested “actions” of this plan, broken down by sector (Municipal, Residential, Business, Education). There are sub-sections within each sector that organize energy-conservation actions by categories such as the built environment, transportation, natural resources, and financial tools. People looking for suggestions on how to take action on specific topics can quickly scan the sub-headings to find the most relevant actions. Many of the suggested actions are linked to web resources with more information about how to carry out that specific action. Additional information is included in the six appendices.

Chapter 1: Background to the Action Plan

Cool Monadnock

The Cool Monadnock project was a three-year regional approach to developing climate and energy solutions at the municipal level. Much of the impetus for the project came out of the 2007 Carbon Coalition campaign for municipalities to adopt local resolutions to implement climate change solutions. Noting that a high concentration of municipalities in the Monadnock region passed these resolutions, three partner organizations, that now form Cool Monadnock, developed a proposal to assist the communities to move forward with their stated intentions of proactively managing energy issues at the local level.

Cool Monadnock, a project of Clean Air-Cool Planet, Antioch New England Institute, and the Southwest Region Planning Commission (SWRPC), was designed to assist Monadnock municipalities in becoming project ready for energy conservation by taking an inventory of energy use for municipal operations and identifying priorities for energy reduction; supporting the development of Local Energy Committees and building member capacity through educational workshops and networking, and developing a regional climate and energy action plan to guide further municipal and regional steps toward energy management and independence. The project was primarily funded by a three-year grant from the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation.

See the appendices for details on the activities carried out by the Cool Monadnock project and further information on the partner organizations.

Chapter 2: Community Consultation

The Neighbors Helping Neighbors Gatherings and Forum

The foundation of the Monadnock Energy and Climate Action Plan was a community consultation process to assess local priorities and capture ideas and insights from local citizens. The community consultation was not open-ended but instead started with the 2009 New Hampshire Climate Action Plan (NHCAP) as its point of departure. The NHCAP was developed through a lengthy state-wide citizen consultation process, spearheaded by the Department of Environmental Services, and organized and honed by science and policy experts. In order to create a regional plan that would reinforce and support the implementation of the NHCAP, the Cool Monadnock team began by selecting 17 of the 67 NHCAP recommendations. The 17 recommendations were selected based on their relevancy to the Monadnock Region and could be implemented at a regional or local level.

The Cool Monadnock team developed a template for a 90-minute group process designed to lead groups of 8 to 15 people to prioritize the most “feasible” and “effective” 2 of the 17 recommendations, and then generate specific ideas about how these recommendations could be carried out locally, and identify groups and stakeholders to take part in the implementation. 1 The Cool Monadnock team then assembled a group of about 15 local “leaders” in September and October of 2009 to review the proposed community consultation process, learn how to host the conversations, and brainstorm venues for the conversations. Leaders included chairpersons of local energy committees across the Monadnock region as well as local planners, representatives of non-profit organizations and businesses known for their efforts to reduce energy costs and support quality of life, and local scholars.

Over the course of the winter (November 2009 – April 2010), the Cool Monadnock team and the group of local leaders organized and held 17 conversations known as Neighbors Helping Neighbors gatherings. Over 100 Monadnock citizens voiced their opinions through this process. A capstone event, the Monadnock Energy and Climate Forum was held on April 28, 2010. At this event, about 40 participants learned about the priorities that had been identified through the community consultation process and then broke into five groups to develop further recommendations about how to mobilize the regional community to reduce energy consumption and dependence on non-renewable energy sources. These groups developed ideas around the areas of education and outreach; renewable energy technologies; forests and farms; transportation and land use; and buildings.

Citizen’s Priorities

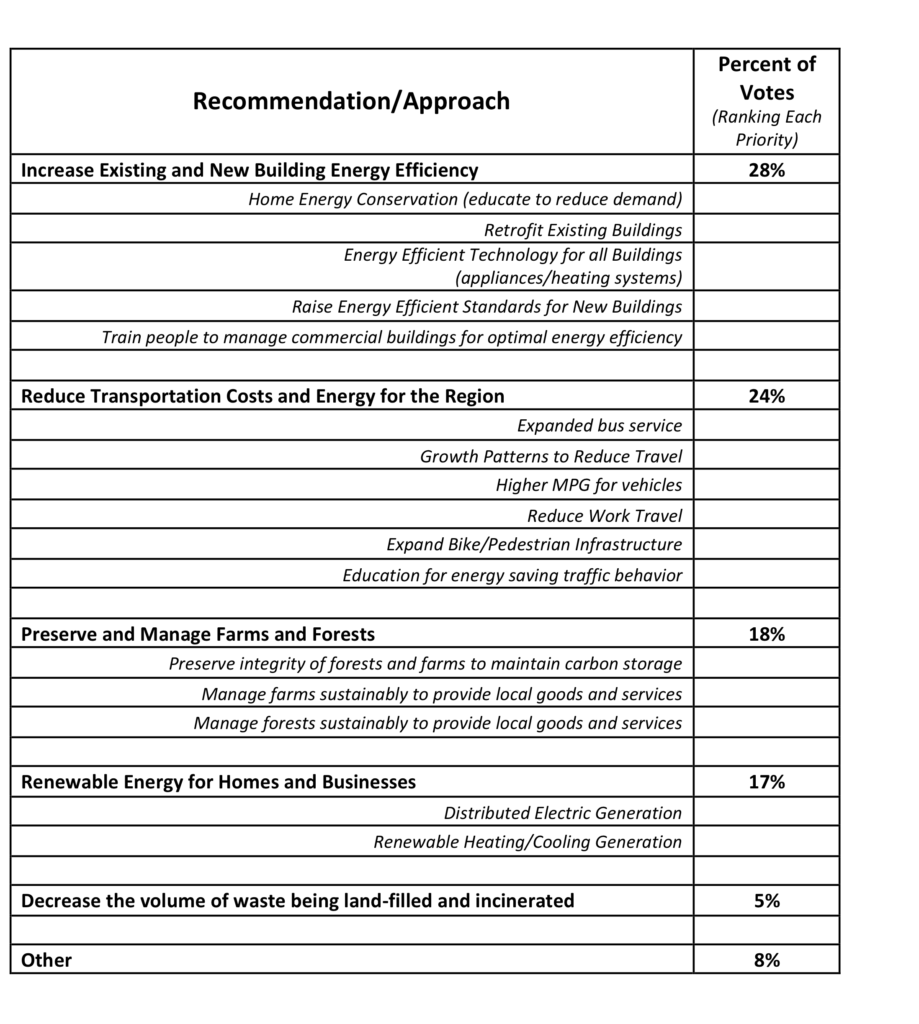

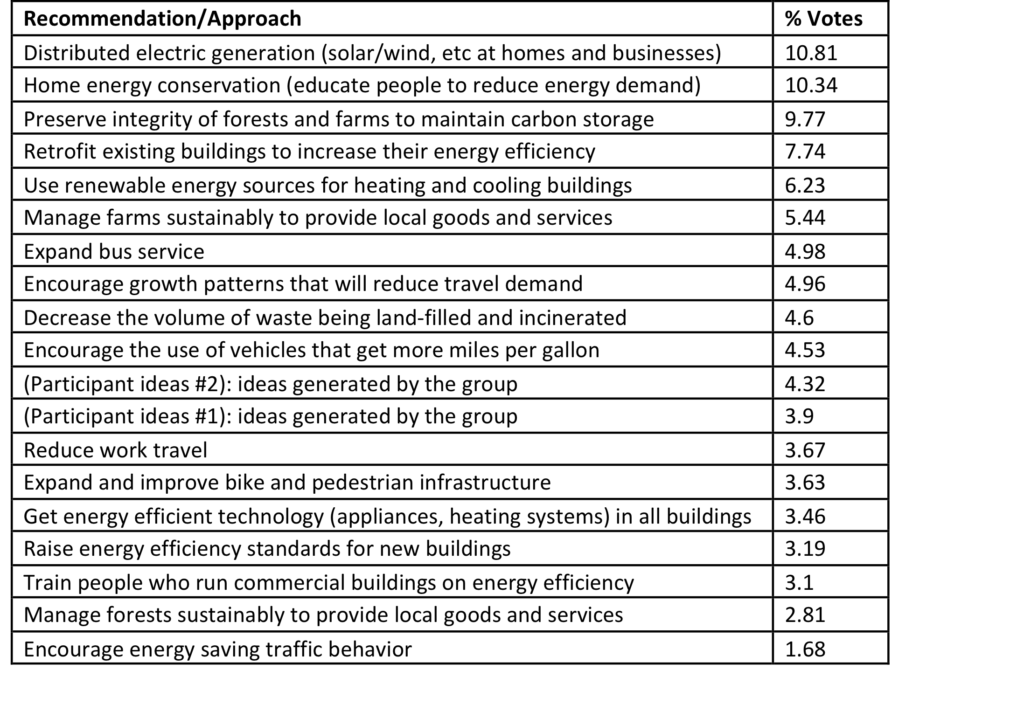

During each gathering, participants were asked to rank the priorities (individually and as a group – see Appendix D for the participant packets) according to which ones they considered to be most feasible and effective. The following table shows a summary of the aggregate results. Under each main recommendation, specific strategies are listed in their priority of importance based on the gatherings.

It is clear from the table above the priorities for action in this region involves increasing existing and new building energy efficiency. The majority of stakeholders expressed their preference to implement actions that would educate homeowners on how to reduce energy usage and to concentrate efforts on retrofitting existing buildings.

It is clear from the table above the priorities for action in this region involves increasing existing and new building energy efficiency. The majority of stakeholders expressed their preference to implement actions that would educate homeowners on how to reduce energy usage and to concentrate efforts on retrofitting existing buildings.

The second highest identified priority for the region was to reduce transportation energy and costs. The two highest strategies to accomplish this priority were identified as expanding bus service throughout the region and creating and maintaining growth patterns that reduce travel.

All of the above priorities have been incorporated into the action plan. The action plan has been organized in a topical fashion as well as in order of early action steps and longer range options. Some action steps were included that did not come up during the community consultation, but are found in other regional and municipal action plans and are known to be effective measures for energy conservation.

After each group had identified which recommendations or “approaches” to reducing energy costs they felt would be most feasible and effective, they then generated ideas about how – what specific projects, programs, actions, etc – to accomplish the top recommendations of their group. The Monadnock Energy and Climate Forum of April, 2010, contributed another very useful set of recommended actions for this plan. The detailed results can be found in Appendix E. Later analysis shows that actions and programs described under one approach for one group would often be described under another approach by a different group. Some of the recommendations were strongly supported within a particular gathering as well as across a number of gatherings, while some suggestions came up only once or twice.

To better guide the development of this plan, the suggestions have been organized according to the four sectors of the plan: municipal, residential, business, and education. The following chapters detail specific implementation measures to reduce energy and greenhouse gas emissions in the four sectors.

1 Leaders were to explain that “feasible” means something for which logistical barriers, such as finding finances, acquiring appropriate technologies, accessing technical assistance, etc, would be manageable, and “effective” means something that will significantly reduce energy use and carbon. Feasibility and effectiveness were emphasized as the prime criteria for all recommendations.

ACTIONS BY SECTOR

Chapter 3: Municipal Actions Sector

Municipal Sector Actions

Municipal entities play a key role in decisions that influence the level of energy consumption within their borders and beyond. The municipal government plays its role by setting both an example and a whole suite of policies and planning decisions that influence the businesses, institutions, and residents in their jurisdiction.

The Built Environment

Municipal Operations. All Monadnock municipalities are encouraged to develop an energy management plan for municipal operations.

- Conduct a baseline energy inventory of municipal energy use, including an analysis of energy conservation priorities. (short term)2

- Develop an energy management plan, identifying specific energy reduction steps, a timeline for accomplishing those steps, and comprehensive funding strategies. (short term)

- Annual reports on progress, including follow-up inventories to measure energy reductions achieved. (short term and beyond)

- The plan should recommend that any new construction, capital improvements, or renovation work of municipal owned buildings should be designed with energy conservation as the highest priority and reflect best practices in building science and high performance building, starting with goal setting and integrated design planning at the conceptual stage, with consideration of alternative and renewable energy sources for electrical power and heating. (short term)

- The plan could recommend that BPI certification should be required for facilities managers, maintenance staff, or anyone responsible for building maintenance to ensure quality control. (short term)

2 Short term = 1-3 years; medium term = 4-8 years; long term = greater than 8 years to implement the strategy. Short-long term = on-going.

Municipal Buildings. With local taxpayers covering the cost of energy for municipal operations, municipalities have a great opportunity to reduce the tax burden by increasing the energy efficiency of their buildings. To increase building efficiency, municipalities are encouraged to:

Conduct a building audit. There are currently several options for undertaking building audits. Municipalities can hire certified professionals (BPI and/or HERS certification is recommended) to conduct either a decision-grade or an investment-grade audit. A decision-grade audit offers a complete picture of energy use in the building, including analysis of the building envelope and heating system. An investment-grade audit builds on the decision-grade audit with support in putting out bids for the recommended retrofits to the building. Another program currently available in New Hampshire is the Energy Technical Assistance and Planning program, which offers overview walk-through analysis of municipal buildings, leading to identification of top priorities for building energy conservation. (middle term to complete all municipal building stock)

Set operations policies. It is recommended that municipalities adopt operations policies in the very short term in order to save energy right away with little or no initial investment. Operations policies include:

- Turning off all unnecessary lighting and equipment when not in use.

- Using energy management software, power strips, or other methods to ensure electrical equipment is not drawing standby power when not in use.

- Installing sensor-lighting.

- Replacing incandescent bulbs with compact fluorescents, LEDs, or other efficient technologies.

- Replacing old equipment with Energy Star models.

- Reducing the number of operating hours of offices.

- Managing or programming thermostats to reduce heating and cooling demand.

- Zoning heating areas of a building.

- Closing off and not heating unused areas of buildings.

- Shift electrical use to non-peak periods.

- Winterizing buildings.

- (short term)

Municipal Fleet. Vehicle fleets are typically the second-largest energy user in Monadnock municipalities. Municipalities have a number of options for reducing energy consumption from their vehicle fleet:

- Track fuel use by individual vehicles. (short term)

- Set vehicle operations policies, such as:

- No idling

- Setting efficient work routes, including not coming to the office for lunch

- (short term)

- Appropriately deploy vehicle fleet technologies such as:

- Idle right units

- GPS systems

- Engine block heaters for emergency vehicles stored in cold buildings (medium term)

- Incorporate renewable or more efficient fuels into vehicle fuel mix

- Biodiesel

- Compressed Natural Gas (may include multi-town co-op to set up a station) (medium-long term)

- Replace older vehicles with more efficient vehicles that get high MPG and/or use alternative technology (i.e., hybrid vehicles). (medium-long term)

- Become involved in the Granite State Clean Cities Coalition to learn more about fleet efficiency. (short term)

Street Lighting. Municipal lighting, including street lights, traffic signals, ornamental lighting, and other sources such as ball fields, is an area of municipal operations that can offer unexpected energy saving opportunities. It should be noted that per energy unit (Btu), electricity is more costly in New England than heating and vehicle fuels. Therefore, efficiency measures in street lighting often leads to very significant cost savings. Efficiency opportunities include:

- Street lighting reductions. Identify unnecessary streetlights in the municipality and have them removed, or, reduce number of hours particular streetlights are turned on. (short term)

- Fixture replacement. Replace necessary streetlights and signals with energy efficient technology, such as LED. (short-medium term)

Water Works. While expensive to upgrade or replace, water pumping stations, waste water treatment plants, and municipal drinking water systems can realize significant improvements in efficiency.

In those municipalities that operate wastewater treatment and public water supply systems, the infrastructure typically includes a number of pumping stations as well as other energy-intensive equipment. There is a great deal of opportunity for energy conservation at various stages in the system. Clearly, proper observation and analysis of the current system is the first step toward making appropriate upgrades to improve efficiency. See this program example from Connecticut, with a list of resources.

Green Power. The various options for obtaining electricity from more renewable and local sources require more long-range planning and larger investment, but offer important opportunities for energy security and independence, better control over energy costs, and significant reductions in carbon emissions. Municipalities should start now to chart a course toward increasing their access to electricity from renewable sources.

- Develop a community-owned renewable power plant. The Interstate Renewable Energy Council recently released a short and helpful guide on community renewable opportunities and issues. (medium-long term)

- Purchase renewable power co-operatively (medium term)

- Lobby local utility to provide more electricity from renewable sources (short term)

Codes and Policies. Municipalities influence the energy efficiency of the local built environment through the setting of local codes and policies as well as through long-range planning activities.

Policy Review, Planning, and Zoning. Many policies and development plans have been adopted without consideration for the rising costs of energy, therefore many policies inadvertently inhibit the municipal government from taking appropriate actions to reduce their energy costs. To address these issues, it is recommended that municipalities:

- Review the EPA’s Smart Growth Guide for guidance and ideas on how to do municipal planning with the goal of energy conservation or the Innovation Land Use Planning Techniques guide prepared by NH Department of Environmental Services in partnership with NH Association of Regional Planning Commissions, NH Office of Energy and Planning, and the NH Local Government Center.

- Conduct a policy and land use audit to identify items that conflict with the goal to save energy. The Keene, NH Land Use and Energy Policy Audit is an excellent recent example. (short or medium term)

- Update the municipal Master Plan with an energy chapter, or attention to energy conservation throughout the document. (short or medium term)

- Consider zoning a concentrated mixed use area within the municipality such as the Sustainable Energy Efficient Development (SEED) District proposed in Keene. (medium term)

- Create zoning that supports smaller homes and small home-based businesses. Land use planners have developed concepts such as Open Space Residential Design (clustered residential units with shared open space and habitat conservation) and Performance Zoning to work toward these goals. They may be applicable in particular Monadnock municipalities. (medium term)

- Organize a Sustainable Design Roundtable across the region. This is an approach to exploring ways in which a state/municipality/region can actively promote sustainable design practices in public building projects and projects receiving government aid or oversight. (short term)

- Encourage the development of quality work-force housing located near work centers. (medium to long term)

- Conduct Health Impact Assessments, including assessments of potential carbon emissions impacts, of new project proposals and land use changes. Here is an example from the West coast.

- Manage transportation demand within and around the municipality

- Collaborate with the Monadnock Regional Transportation Demand Management Association (short term)

- Create a baseline study of current commuting distances with a goal for reduction (short term)

- Join other regions in a competition to reduce transportation demand and vehicle miles traveled (VMT)(short to medium term)

- Get grant funding to carry out programs (short to medium term)

- Instate a municipality-wide anti-idling policy (short term)

- Green Building Codes. Municipalities can set codes for building standards that go beyond codes and standards applied at the federal and state levels. When updating building codes, municipalities should:

- Dialog and partner with local builders, architects, HVAC engineers, local businesses and materials supplied manufacturers, Local Energy Committees, and other active citizens. (short term)

- Review the best practices available in the wider market. (short term)

Financial Tools. Municipalities can influence local energy efficiency through a variety of financial tools. These tools include the grants and programs that the municipality can use for its own energy conservation initiatives as well as programs that the municipality can adopt and offer to its constituents. As a government entity, the municipality can also use taxes and fees to encourage or discourage particular activities, therefore influencing energy use patterns in the area.

Revolving Loan Funds and Property Assessed Clean Energy. These are financial tools whereby municipalities set aside capital and then loan it out to local residents and businesses to carry out energy efficiency projects or install renewable energy technologies on their property. Enabling legislation for Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) was passed in New Hampshire in May of 2010. Under this legislation, municipalities are enabled to individually establish a fund to be used for PACE loans to residents and/or businesses in their jurisdiction. These loans, which allow residents and businesses the opportunity to access measures and technologies that will lead to significant energy savings, without having to lay out the high initial costs of purchasing and installing the technology. The loan from the municipality can then be repaid through an additional assessment connected to the payment of property taxes. If the property, along with the energy efficiency upgrades or technologies, is sold before the loan is repaid, the loan is transferred to the new property owner. More information on the PACE program in general is available here. Information about the program in New Hampshire is available here.

- Pass local PACE adoption legislation and establish a revolving loan fund. (short to medium term)

- Carbon taxes or fees. Municipalities can use taxes or fees to discourage or encourage people from activities that waste or save energy.

- Assess a tax on businesses that use drive-through windows because it encourages their customers to idle their vehicles (short term)

- Increase parking fees & provide free parking for car pool and alternative fuel vehicles (short term)

- Provide other grants or financial incentives for local businesses and homeowners to reduce energy costs. Municipalities in NH offer property tax exemptions for solar energy, wind power, and wood heating energy. A list of current exemptions by municipality is available here. Those municipalities not currently offering a full battery of exemptions can expand their offerings to encourage alternative energy adoption. (short term)

- Increase Access to Subsidies. Based on income guidelines, a segment of the population currently has access to energy conservation programs such as home weatherization to save heating costs. Municipalities can work to increase the number of citizens who can take advantage of these helpful programs.

- Discuss with the state the potential to change income guidelines for home energy efficiency subsidies (short term)

- Shift guideline from 200% to 250% of poverty level

- Ensure residents have access to loans without large fees

- Provide information to residents about how to apply for home energy efficiency programs from federal and state agencies, as well as the local utility (short term)

- Provide bridge loans to fill in gaps between bank loans and resident’s needs for energy efficiency projects. Collaborate with local banks. (short-medium term)

Community Leadership. The municipal government holds a leadership role within the community from which it can launch community initiatives, recognize and publicize positive role models, and provide services to the wider community.

Energy Challenges. Energy “Challenges” are often volunteer programs developed by non-profit and other citizen organizations. However, municipalities play a key role by endorsing and promoting challenges, or in many cases, “joining” a challenge whereby a group of citizens in one town are set up to race against another town to see who makes the greatest reduction in energy use.

- Join or endorse the “10% Challenge.” This is a voluntary program for businesses that is currently operating in Keene, NH. It offers guidance and recognition to businesses that measure and reduce their energy use. It is recommended the Challenge is expanded to allow for participation by businesses outside of Keene but in the Monadnock area. In order to implement this, it is suggested the Keene Chamber of Commerce consider assisting in administering the Challenge in partnership with the City of Keene. The Challenge could be expanded to include quarterly convening’s of participants in order to network, provide the latest information on energy reduction solutions and technologies, along with the creation of a web site that includes best practices of businesses in the region. (short term)

- Join or endorse the New England Carbon Challenge. This is a web-based residential program that allows families to track and reduce energy use at home. Many New England towns have celebrated friendly “competitions” with one or more other community in which they challenge one another to a race to reduce the greatest proportion of energy use. Interested communities can go here to get started. (short term)

- Create and publicize an annual award to recognize local home owners, landlords, and businesses that show the best models for energy conservation. (short term)

- Schools. While New Hampshire public schools are operated by school boards (school administrative units), the funding for them is collected through property taxes. Therefore, the municipality is connected to decision-making related to expenditures and can open lines of communication and advocate for energy reductions in school operations.

- Encourage local schools to adopt energy management planning including building audits, weatherization, and retrofitting. Several organizations that provide these services to schools can be accessed in the Monadnock region, including The Jordan Institute and TRC Solutions. (short-medium term)

- Any new school buildings should be designed to the highest energy efficiency standards with consideration of alternative and renewable energy sources for electrical power and heating. (short term)

- Encourage school district to audit transportation routes, vehicles, and fuels and plan for improvements to reduce energy use. (short-medium term)

- Efficiency Technology “Bank.” Many Monadnock residents advocate having centralized “banks” that would maintain equipment that can be used by local residents and businesses to assess their energy efficiency and make small do-it-yourself improvements. It is usually suggested that the “banks” be housed in the local library, and the public works department. Items for residents would be stored in the local library while items for professional energy auditors such as a thermal imaging camera or blower door kit would only be available at the public works department for certified auditors.

- Purchase a suite of energy efficiency equipment such as a “Kill-a-Watt” appliance energy use meter, a thermal imaging camera, a blower door kit, maybe a tall ladder, and make it available on loan to local residents or businesses. (medium-long term)

- Educate Permit Seekers. Municipalities authorize new construction projects as well as major additions and upgrades by issuing permits. This provides a useful interface for educating the relevant public not only about new building code standards, but also about why and how to increase the efficiency of the proposed building project.

- Provide education on building energy efficiency and optimizing building orientation (with or without a certification) along with any building permits. (short term)

- Support Employee Travel Reduction. As businesses develop creative employment models, including more and more “telecommuting” or working from home, municipalities can take measures that better enable these more efficient models.

- Ensure full internet coverage across the municipality (medium term)

- Make public spaces available and affordable for occasional conferences and meetings (short-medium term)

- Support shared vehicle programs such as ZipCar (medium term)

Public Transportation. Larger municipalities operate their own public transportation systems while smaller communities work with regional systems, often from private operators. As such, transportation in the Monadnock region involves individual municipalities to a degree, but also involves regional collaboration.

- Partner with public and private regional partners such as the Eastern Monadnock and Cheshire County Regional Coordinating Councils for Community Transportation www.swrpc.org/trans/rcc6.htm andwww.swrpc.org/trans/rcc5.htm to expand public transportation service. The increased service should feature better accessibility, including more regional connections, as well as more interfaces with other transportation modes such as bike and walking paths (on-bus bike storage), park and ride, etc. (medium-long term)

- Promote rider incentives such as affordable fares and frequent rider discounts as well as WiFi. In the current market, incentives help riders who have transportation options choose public transportation (which reduces energy emissions and improves community health). (medium term)

- Lay the proper groundwork for an effective system: research local transportation demand, needs, and best practices; educate the community and create “buy-in”; obtain funding (a graduate student can help with grant writing). (short term)

Natural Resources. Municipalities directly and indirectly manage and impact the natural resources with their jurisdictions. They can take specific measures to promote the healthy maintenance and regeneration of the local natural resources, including working resources such as farms.

Preserve Farms and Forests. Municipalities, through their own commissions (i.e., Conservation Commissions) as well as in partnership with Land Trusts, conservation agencies, cooperative extensions, and other groups, play a key role in preserving the important resources of local farms and forests.

- Conduct a natural resources inventory to assess what resources are currently present, as well as identify issues such as threatened water supplies or habitats, soil degradation, etc. (medium term)

- Create a local farm policy to ensure farming is conducted in a manner that is sustainable within the context of the local climate, geology, etc and encourage conservation of prime agricultural soils in perpetuity. (medium-long term)

- Promote thriving natural resources within urban areas by expanding municipal green space, tree planting, rain gardens, and community vegetable gardens. (short-medium term)

- Promote farmer’s markets, agri-tourism, and farm education programs. (short-medium term)

- Promote conservation planning on a municipal basis, identifying key natural resources for conservation. (mid term)

Optimal Waste Management. The health of natural resources is highly impacted by the policies and practices of waste management, which is handled by municipal entities or private haulers guided by municipal policy. Potential options include:

- Make recycling mandatory, educate citizens on recycling, and instate zero-sort recycling. (short-medium term)

- Capture energy from the landfill through systems like biochar and methane recovery. (medium-long term)

Chapter 4: Residential Sector Actions

Residential Sector Actions

Household decisions, including how people live in their homes, daily commutes and transportation decisions, and volunteer neighborhood activities, account for a significant segment of energy use. By the same token, efforts to reduce energy use at home have a direct impact on the people making the choices to save energy. The efforts and the pay-back are closely tied together.

The Built Environment – Direct Action

Energy Efficient Homes. A range of options are available to homeowners as well as renters who want to save energy at home with small to moderate investments.

- Start by using a web-based tool such as MyEnergyPlan.net to measure current energy use, plan personal energy reductions, and access resources. (short term)

- Adopt behavioral measures to reduce energy use such as turning off lights, unused appliances, and turning down thermostats. Replace light bulbs and appliances with energy efficient technologies. (short term)

- Weatherize your home. (short term)

- Have a professional audit of your home. It is recommended that homeowners consider utilizing an energy auditor that is BPI certified to quality control. The following site has information on energy audits: www.energycircle.com(short-medium term)

- Hire qualified contractors to carry out deep retrofit projects. (medium term)

- Build new homes to highest energy conservation standards or join (affordable) co-housing communities. (short term)

Energy Raisers. Energy Raisers are collaborative efforts to carry out energy projects in a number of homes. A group of local citizens, each of whom wants to make similar energy efficiency upgrades in their own homes, gather at one of the homes and work with a professional who teaches the whole group to carry out the work. The entire group provides the labor to carry out the work in the first home, as well as each of the other homes. Homeowners need only purchase the materials for the project. See the Plymouth Area Renewable Energy Initiative website for more information.

- Convene an Energy Raisers group to do Home Weatherizations. (short term)

- Convene an Energy Raisers group to install Renewable Energy Technologies (i.e., solar hot water heaters) (short-medium term)

- Green Purchasing Co-ops. Groups of residents may be able to realize savings by purchasing energy conservation goods and services in bulk deals.

- Create a co-op to purchase goods such as weatherization materials, renewable technology (such as solar panels), or renewable fuels. (medium term)

- Negotiate bulk deals for services such as home energy audits. (short-medium term)

- Investigate co-op models or other options for obtaining renewable electricity. (medium-long term)

The Built Environment – Capacity Building

Citizen to Citizen Education. Information about how to create a frugal personal energy budget is well suited to being shared through social and civic networks. Early adopters, advocates, and professional trainers can reach interested citizens through neighborhood associations, civic groups, social clubs, faith communities, service organizations like the Rotary, and other similar networks.

- Share information and technical knowledge about resources and methodologies to help citizens reduce energy use at home. (short term)

- Reach peer groups through gatherings (house parties), online communities (facebook, web-clouds, social marketing), local newspapers and newsletters, public events (like change a light day, local festivals), invited speakers and demonstrations, contests (like Biggest Loser or the New England Carbon Challenge), or by “peer pressure,” i.e., asking neighbors to turn off unnecessary lights. (short-medium term)

- Landlords. Rental properties often run the risk of being overlooked for “unnecessary” upgrades targeted toward energy conservation. Especially when tenants are responsible for heating costs, the property owner does not perceive a motivation for energy investment. However, these investments will increase the value of the owner’s property, and property owners can protect that value by educating tenants.

- Evaluate, weatherize, and retrofit rental properties to increase energy efficiency. (short-medium term)

- Create a network of landlords to share information and resources. (short term)

- Educate tenants on energy conservation practices. (short term)

- Have tenants cover energy costs separately from their rent. (short term)

- Citizen Advocacy. A key step in taking energy conservation actions at home is ensuring that the proper governmental policies and programs are in place to support and facilitate those actions.

- Attend planning board meetings, select board meetings, City Council meetings, and any relevant sessions to advocate for codes and policies that support energy efficiency. (short term)

- Contact decision-makers to advocate for financial incentives to help residents accomplish energy efficiency projects. (short term)

Transportation

Reduce Personal Travel. Households can employ a variety of strategies to reduce the number of daily vehicle trips in a (single occupancy) personal vehicle.

- Carpool. Use a web-based ride share community. (short term)

- Reduce work travel by arranging to telecommute for all or some days. (short-medium term)

Natural Resources

Eat More Local Food. Our national food system uses energy inefficiently in two major ways. Conventional agricultural practices are energy intensive because they require large energy inputs for fertilizers, pesticides, irrigation, and large farming equipment. Secondly, large amounts of fuel are expended to transport farm produce long distances from where they are grown to where they are consumed. Household food choices have a strong impact on the amount of energy used to produce food as well as the impact that type of agricultural practices used for food production and the impact of that on the surrounding resource base.

- Start a community garden with composting. (short-medium term)

- Ask the municipality for use of public space.

- Become a Cooperative Extension Master Gardener. (short-medium term)

- New housing developments should have garden space. (medium-long term)

- Start a permaculture edible forest garden. A NH-based example of regional support for this approach is from theNashua Regional Planning Commission. (medium term)

- Advocate for Sustainable Land Management Practices.

- Get involved in municipal land use planning. (short term)

Chapter 5: Business Sector Actions

Business Sector Actions

The business sector includes the wide spectrum of the world of work, including manufacturing, retail, services, non-profit organizations, faith based institutions, and agricultural businesses. All members of the business sector can make common contributions to energy conservation, while some contributions can best be made by particular segments of the business community.

The Built Environment

Reduce Energy Use In-House. The steps businesses can take to reduce energy use in-house depend in large part on the type of business in question. Many of the steps available are the same ones that people can take in their residential homes, assessing current energy use, adopting energy conservation behaviors, and weatherizing and retrofitting the buildings. In some businesses, more specialized considerations need to be made, including production procedures, technologies, and materials.

- Join the 10% Challenge Program. The 10% Challenge is currently a voluntary program available in Keene, NH, which provides guidance and recognition to businesses that take voluntary measures to reduce their energy consumption. Monadnock businesses outside of Keene can work together to create 10% Challenge programs in their own towns or expand the Keene Challenge to the rest of the region. It is recommended in the municipal sector (Chapter 2) the Challenge program is expanded to create a network of participants with educational convening’s, networking opportunities, and examples of best practices. (short term)

- Retrofit the place of business to improve energy efficiency. (short-medium term)

- Install Smart Metering.

- Install Motion Detector Lighting.

- Join a green purchasing co-op to get bulk pricing on energy efficiency products such as renewable fuel, energy efficient (Energy Star) equipment and appliances, weatherization products such as insulation, and other products. It is important to note that biofuel is currently available in the region for medium to large heating applications. A short term action specific to this would include the education and outreach about this availability to businesses. (medium-long term)

Transportation

Reduce Employee Work Travel. Employers can greatly reduce the region’s Vehicle Miles Traveled by structuring their employee’s work in a way that reduces travel and helping provide the infrastructure that will enable a reduction in travel for work.

- Support Broadband expansion efforts in order to allow more people to work from home. (short term)

- Provide affordable conference spaces. (short term)

- Invest in a shared “ZipCar” system. (short-medium term)

- Provide recognition to good models. (short term)

- Structure employee schedules to reduce work travel. (short-medium term)

- Efficient Work Travel Options. Where travel to work is necessary, employers can take steps to encourage that employees use efficient means to travel to work.

- Set up a carpool or vanpool system for employees. (short term)

- Create a parking space cash-out program. (short term)

- Support Public Transportation. Businesses should participate in public discussion and planning of an effective public transportation system in the Monadnock region.

- The Monadnock Region Transportation Management Association is the appropriate convener of regional discussions about public transportation.

- Other groups should be involved in developing the transportation system, including Southwest Region Planning Commission, the Regional Coordinating Councils for Community Transportation, the Antioch and Keene State College Green Bikes Program, local biking and pedestrian groups, schools, businesses, private transportation service providers, and municipal representatives (Conservation Commissions, Open Space Commissions, Planning Boards, Local Energy Commissions). (short-medium term)

- Encourage businesses and shopping centers on the outskirts of Keene to allow free parking spaces to be used for public transportation. (short term)

Community Engagement

Marketing and Public Awareness. The business sector is well positioned to influence and educate the public about energy conservation.

- Start a “Go Green Monadnock” marketing campaign to raise awareness about reducing energy use and increase public “buy in.” (short-medium term)

- Built networks of business partners and customers

- Communicate a common message through business forums, Rotaries, NHBSR, etc.

- Create a Monadnock Region “Green Alliance” like one in the New Hampshire seacoast region that is designed as a business-to-business mentoring program to promote sustainable and green business practices.

- Industry Standards. Business entities are well positioned to help develop standards for energy efficiency in products, buildings, and processes.

- Develop industry standards for energy efficient buildings. (medium term)

- Professional Training. Energy efficiency careers, often labeled “green collar” jobs are a growing field of employment. The business sector can actively contribute to the development of this promising opportunity.

- Provide funding, scholarships, and internships for students in green collar fields. (medium-long term)

Natural Resources

Re-Use Existing Facilities. The development of new business ventures should avoid converting natural habitat and prime agricultural land to industrial uses.

- Plan to redevelop previously occupied properties when developing new business ventures. Specifically encourage Monadnock Economic Development Council to incorporate this into their mission. (medium-long term)

- Forest and Agricultural Land Policy.

- Develop a sustainable practices policy for forest and agricultural land. (medium-long term)

- Identify natural resource assets in the area.

- Gather input from farmers and the wider community.

- Help develop agricultural commissions.

- Educate the community and encourage citizen science. Work with natural resource professionals to encourage understanding and use of Best Management Practices.

- Build a diverse network of partners: Monadnock Conservancy, the Model Forestry Policy Program, Land for Good, (these first three could be the champion organizers of the effort), Monadnock Farm and Community Connection/Cheshire County Conservation District, Hannah Grimes, Valley Food & Farm, Southwest Region Planning Commission, the Sustainability Project, Community Support Agriculture farms, The Forest Society (SPNHF), Ashuelot River Local Advisory Committee, The Nature Conservancy, Cities for Climate Protection Committee, Natural Resources Conservation Services, Cooperative Extensions, Antioch University New England, Keene State College, Franklin Pierce University, high schools, elementary schools, Harris Center, Working Families Win, and the Monadnock Sustainability Network.

Economic Incentives.

- Invest in local carbon offsets – pay local people to maintain the ecological services of healthy working farms and forests. (medium term)

- Create short and long term economic incentives to keep working farms and forests intact. (short-long term)

- Gather and distribute information about the real costs of losing these resources.

- Develop a local currency.

- Work with partners including the grassroots as well as policy makers. Work with conservation commissions, Monadnock Buy Local, and Hannah Grimes.

- Advocacy Networks. Natural resources and land issues tend to be out of the scope of the “public mind,” so it is more important to create strong networks and collaboration among organizations working on forest and farm issues.

- Enlist educational institutions to hold forums and educational events. (short-long term)

- Develop a network of organizations. Find a way to share calendars and contacts databases in order to better coordinate activities. Groups to engage include the Sustainability Project, educational institutions, Cheshire County Conservation District, Hannah Grimes (the first four would be good champions for the project), Advocates for Community Empowerment, Southwestern Community Services, Monadnock Developmental Services, Monadnock Family Services, Cheshire Mediation, Rotary Clubs, Cooperative Extensions, Faith Communities, Cities for Climate Protection Committee. The Monadnock Sustainability Network is planning a summit of leaders in sustainabity. Ensure the above organizations are included in the summit. (medium term)

- Review various models of working on the issues (short-medium term)

- Monadnock Conservancy land stewardship program

- Internet based vs. Vital Communities model

- Arts Alive model

- Time shares

The Non-Profit Sector

Citizen Education. The non-profit sector is well positioned to provide adult education through non-traditional avenues.

- Partner with school teachers and adult educators, planning boards and conservation commissions, land trusts, faith communities, employers, unions, government representatives, local energy committees, real estate agents and home owners, the Office of Energy and Planning, the Southwest Region Planning Commission, the local media, builders, local businesses, student “green” clubs. (short-medium term)

- Partner with municipalities to enhance community education about local issues related to energy: (short-medium term)

- Develop tools and information on local climate adaptation priorities and programs

- Publicize local and regional success stories about energy conservation

- Educate the public about various aspects of energy conservation (short-long term)

- Why and how to increase energy efficiency

- Currently available resources for reducing energy use as well as technologies

- Latest information on renewable energy (solar, wind)

- Sustainable forestry practices

- Comprehensive information on bio-fuels (life-cycle costs, energy ratios, food crop displacement, transportation costs)

- Up-to-date climate science information

- Host Button-Up workshops on home energy savings.

- Non-profit organizations can contribute to public education in a variety of ways (short-long term)

- Make presentations or give workshops at institutions of higher learning (Keene State College, Antioch University New England, Franklin Pierce, River Valley Community College)

- Prepare curriculum to be used by partner educators (adult educators, school teachers, professional trainers)

- Hold or participate in conferences: the Green Building Open House, the Local Energy Solutions Conference, Biannual regional Local Energy Committee meetings, Local Energy Committee Roundtables, home shows, etc. (Vital Communities has a successful model of LEC roundtable discussions held several times a year).

- Provide speakers, trainings, demonstrations, and forums

- Release information through the media

- Develop an internet clearinghouse for energy conservation resources and information (could check out ones like energysavers.com to see what’s out there already). This project could be done with partners like local contractors, the Home Builders Association, New Hampshire Sustainable Energy Association, nonprofits, Antioch student interns.

- Engage in two-way conversations with the “targets” of educational efforts to ensure that the message/information is meaningful to them and leads to positive change.

- Identify community champions, institutions, and partners

- Engage students in service-learning projects

- Consider using the Master Gardener model (affordable training plus public service house to impart or implement the knowledge that has been taught)

- Advocacy. Many non-profit organizations have a specific advocacy mission related to supporting energy conservation.

- Advocate for municipal, state, and federal policies that are favorable to energy efficiency and renewable energy (short-long term)

- Campaign for increased incentives to help citizens, local governments, and businesses afford energy efficiency measures (short-medium term)

- Partner with municipalities to advocate for enabling legislation and programs at the state and federal level for: (short-long term)

- Carbon tax policies

- A policy that favors the use of renewable energy in new government-owned infrastructure projects

- A policy that homes that receive LIHEAP assistance must be provided weatherization

- Accelerate rulemaking at the Public Utilities Commission for renewable energy installations

- Create building standards and lighting standards that emphasize energy efficiency

- Programs. Non-profit organizations also carry out programs to support energy conservation.

- Provide recognition and publicity for good models of energy conservation. (short term)

- Operate “Challenges” that guide groups and/or individuals on how to reduce their energy use and engage them in friendly competition with others to achieve energy conservation goals. (short term)

- Provide services to measure energy use baselines for groups (such as municipalities) and provide them with guidance on prioritizing and reducing their energy use. (short-medium term)

- Partner with municipalities and Local Energy Committees on regional projects such as: (short-long term)

- Create a regional technical resource network

- Create a regional “Green Center” that would be a one-stop shop for educational resources. (Peterborough attempted to receive funding for this with their Armory Maintenance Shed)

- Provide weatherization services for low income residents

- Develop a strategy for sharing resources and skills at the regional level (inventory of resources and skills)

- Support the formation of Local Energy Committees/Commissions

- Identify, create, or make available shovel-ready energy conservation projects

- Advocate that municipalities are enabled to take advantage of low-interest loans for energy retrofits. This has two components: advocate for the availability of low-interest loans for municipalities; and pass warrants that allow municipalities to enter contracts for these loans without having to wait for town meeting. These loans would likely be on the performance contract model, whereby the loan is repaid through energy savings.

Electrical Utilities

- Provide more incentives and grants to customers for energy efficiency. (short-long term)

- Expand current programs. (short term)

- Offer customers an option to purchase green power, expand the use of renewable sources for generating electricity. (short-long term)

Financial Institutions

- Provide accessible loan and mortgage programs for energy upgrades and renewable energy systems (short-long term)

- Provide microfinancing for Energy Star appliances (short term)

- Participate in community discussions around renewable energy (short term)

- PACE/Berkeley model

- Cash neutral loans

- Federal money

- Start a venture capital firm (like the Massachusetts Green Energy Fund) to coordinate investment in green energy technologies. (medium term)

Real Estate

- Educate home buyers about energy efficiency (short term)

- Provide education to realtors through a possible presentation at one of their existing events about energy efficiency (medium term)

Builders and Contractors

- Provide affordable audits or package deals for groups (short-medium term)

- Regard inspectors as expert back-up to carpenters (short-medium term)

- Expand training and re-training in the trades (short-medium term)

- Help develop building efficiency standards (short-medium term)

The Agricultural Sector

- Participate in Farmer’s Markets & Agri-tourism (short-medium term)

- Invest in more greenhouses (short-medium term)

- Train more farmers – spark interest in the field (short-medium term)

Chapter 6: Educational Sector Actions

Educational Sector Actions

The Built Environment

Public school buildings are often among the largest facilities in a community. There are ample opportunities to reduce energy consumption in public school buildings as well as in campus of higher education institutions.

Educational Buildings.

- Undertake a baseline inventory and analysis of school energy use, with priorities to reduce current demand. Many school systems have worked with the Jordan Institute’s Granite State Energy Efficiency program. Another resource available at this time is the New Hampshire EnergySmart Schools Program operated by TRC Solutions. (short term)

- Change the school schedule to reduce the number of heating days (short term)

- Install solar panels and use them as a basis for technical education for students (short-medium term)

- Develop a school based or participate in an existing rideshare program like CVTC’s rideshare board (list hyperlinkwww.cvtc-nh.org)

- Participate in the Safe Routes to School program to encourage and promote pedestrian and bicycling friendly infrastructure, policies and programs for students to safely walk and bike to/from school.

Transportation.

- Limit the availability of school parking for students (short term)

- Include information about vehicle maintenance for energy efficiency in driver education. (short term)

- Enact anti-idling policies on campus. The New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services runs a school-related anti-idling program. Another guiding resource available online is The Idling Reduction Tool Kit. (short term)

The Educational Mission

Energy Conservation Curriculum.

- Students at all educational levels will benefit from developing a solid base of knowledge about energy.

- Work with non-profit organizations to develop and integrate energy efficiency into public school curriculum. (short-medium term)

- Engage students in service-learning projects in the community. (short term)

- High schools and institutions of higher learning should develop and offer professional training for energy efficiency careers. Include training in vo-tech programs. Keene State College has offered Building Analyst Training as a continuing education course and offers sustainable design components in their architectural program. More technical training on building science could be incorporated into trades programs such as the construction program at Cheshire Career Center and River Valley Community College. (short-medium term)

- Community Education. Educational institutions can influence the wider community through their students in a variety of ways.

- Host events like science fairs or a “Biggest Loser”-style contest that involves the parents of students and the wider community. Share energy information through school events and publications. (short term)

- Develop models and research around energy and energy conservation including computer software, physical models, scientific models, public presentations and displays of the findings, and sharing findings through social media. (short-long term)

APPENDICES

Appendix A: The Cool Monadnock Project

Foundational Climate Work in New Hampshire

The path to global warming solutions in the Cool Monadnock region starts with the Carbon Coalition.

The Carbon Coalition is a non-partisan coalition of citizens, scientists, businesses, students, communities and organizations, who came together to advocate for a national energy policy that protects our communities and environment from the ravages of global warming caused by carbon pollution.

The Carbon Coalition grew out of efforts by some of New Hampshire’s leading environmental groups, including the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests, Appalachian Mountain Club, Audubon Society of New Hampshire, New Hampshire Public Interest Research Group, and Clean Air-Cool Planet, a Portsmouth-based group specializing in solutions to global warming.

The Carbon Coalition took a major step towards reducing NH carbon emissions with its clarion call, in April 2003, for NH citizens to “put global warming and the damaging health and economic effects of carbon pollution high on the political agenda.” Just a few years later, the Carbon Coalition was the chief force behind the NH Climate Change Resolution, circulated in towns throughout NH in advance of the 2007 Annual Meeting. By May of that year, 164 NH towns had heeded the call.

Wasting no time, the Carbon Coalition created the Local Energy Committee Working Group (LECWG) to capitalize on the success of its climate change resolution initiative. The mission of the Local Energy Committee Working Group is to provide collaborative guidance and technical support to New Hampshire Local Energy Committees seeking to reduce energy use and greenhouse gas emissions within their communities. Over 90 local energy committees (LECs) formed in 2007-2008.

Cool Monadnock Initiated

The same period saw the beginning of Cool Monadnock, a three-year joint initiative between Clean Air-Cool Planet and Antioch New England Institute. Cool Monadnock is a collaborative community mobilization effort, made possible by funding through the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation, that served the towns of the Monadnock Region that are members of the Southwest Region Planning Commission. The majority of the towns in this region passed resolutions at the 2007 Town Meeting to form local energy task forces (e.g., LECs) and to take action on greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction. The goal of Cool Monadnock is to achieve significant reductions in GHG emissions in the Monadnock Region.

Cool Monadnock Partner Organizations

Clean Air-Cool Planet is an action-oriented environmental group working directly with corporations, communities, and campuses to develop and implement voluntary greenhouse gas emission reduction efforts. A 501(c)(3) qualified non-profit organization, CA-CP works throughout the Northeast to provide practical solutions that demonstrate the economic opportunities and environmental benefits associated with early actions on climate change.

Antioch New England Institute (ANEI) is a consulting and community outreach department of Antioch University New England. ANEI promotes a vibrant and sustainable environment, economy, and society by encouraging informed civic engagement. It provides training, programs and resources (U.S. and international) in leadership development, place-based education, nonprofit management, environmental education and policy, smart growth and public administration.

Community Education, Networking and Workshops

With a plan to convert political resolution to action, Cool Monadnock held a kick-off event in Winter, 2008. By spring, additional events were providing community participants with the science of climate change. At the beginning of April, for example, Antioch New England Instituted hosted a lecture on Climate Change in the Northeast U.S.: Past, Present, & Future. Guest speaker was Cameron P. Wake, research associate professor with the Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space at the University of New Hampshire.

In June, Cool Monadnock collaborated with EPA on a Community Energy Forum, held in Keene, NH at Antioch University New England. Attendees learned about the work of the Jordan Institute, a New Hampshire non-profit organization working to implement significant climate change solutions by reducing fossil fuel use in buildings. The forum moved from a discussion of rising carbon emissions and the potential effect in Southern New Hampshire to:

- a review of NH energy cost data (showing upward changes);

- an introduction to conducting a building energy assessment (using Portfolio Manager software);

- a demonstration of how reducing energy costs and carbon emissions might both result from increased energy efficiency in public buildings (e.g., schools); and, finally,

- an overview of ways to achieve greater efficiency.

In August 2008, the Carbon Coalition Local Energy Committee Working group and the NH Department of Environmental Services began a series of four regional round tables, one of which as hosted in Keene by Cool Monadonck. The round tables focused on a discussion of the Governor’s Climate Change Policy Task Force. The purpose of the round tables was to gather Action Plan input from Local Energy Committee members. Members’ ideas about content and implementation of an action plan were of special interest.

At a Breakfast Roundtable in February 2009, citizens, government officials, and community group leaders shared news, tips, and concerns about their energy efficiency efforts to date. They also gathered to hear Jim Gruber and Christa Koehler, directors of Cool Monadnock, tell them about new avenues for financial support of energy efficiency projects. Federal economic stimulus plan funds and monies from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) would be available for energy efficiency on a competitive basis.

Roundtable participants did some brainstorming around proposal ideas. The Cool Monadnock program offered assistance to those interested in submitting a proposal. Summary notes and a list of project ideas generated at the Breakfast Roundtable went out to all attendees.

Participants in the Breakfast Roundtable made the following recommendations for energy conservation actions (they have been taken into consideration in the writing of this Plan):

SPECIFIC TYPES OF PROJECTS/PROGRAMS

- Municipal retrofits

- A regional technical resource network

- Regional “green centers” – Green Center would be a one stop shop for educational resources.

- Weatherization of non and low income

- Strategy to share regional resources and skills

- First steps: committee formation, inventory and audits, forming an LEC

- Home energy audits

- Shovel ready projects identified, created and made available

- Public transportation (including buses) for local and inter community

- Buses that exist should incorporate bike racks for inter-modal transportation options.

- Training for energy auditors and other programs to create green jobs in region

- Weatherization workshops created for region

- Energy Commissions created by state statute

EDUCATION

- More community education and awareness on conservation and energy efficiency

- Education of forest resource importance

- Education on real impacts of bio-fuels (travel distance, displacement of food, energy ratio)

- Access to up to date climate science

- Develop tools and information on local adaptation

- Publicize success stories in region

POLICY

- Adopt State Climate Action Plan

- State law for consideration of renewable energy in projects

- Requirement for funding for weatherization for homes receiving LIHEAP money must have weatherization

- Carbon Tax implemented

- Accelerate PUC rulemaking (in process) for renewable energy installation

- State legislation and policy created to provide initiatives for building standards and lighting

- Ability to purchase green power from utility

FINANCING STRATEGIES

- Low interest or no interest revolving loan fund for energy retrofits. NH legislation would need to be amended to allow

- Form Buying Group through possibly Cool Monadnock: For example insulation bought in large quantities, etc. This would require funding to Cool Monadnock to buy quantities in bulk to then be distributed to towns at low price due to bulk purchasing

- Create state incentives for small communities to share certain facilities and resources on joint projects

- Support location tax credits

- Allow for a regional entity to disperse low interest loans to towns seeking funds to retrofit town buildings. Loans could be paid back as savings are accrued through reduction in energy usage. Loan would be structured to allow municipality to enter this type of performance contract without having to go through town meeting.

On May 20, 2009, the Cool Monadnock and the Keene Cities for Climate Protection Committee brought together resource people and local leaders and activists at a workshop titled From Data to Action. The resource people had expertise directly relevant to preparations in the Monadnock region to lower energy costs. Their areas of expertise included: audits and retrofitting of buildings, transportation and fleet management, streetlight reductions and retrofits, alternative energy technologies, and education outreach for behavior change.

Baseline Inventories for Monadnock Municipalities

In 2008 and 2009, Cool Monadnock assistants reached out to the 35 municipalities in the region and offered to assist each of them with creating a baseline inventory of their municipal energy usage. Over the course of the two years, twenty of the municipalities responded with the interest and local capacity (municipal staff and local volunteers) to be able to complete the baseline inventory process.

Cool Monadnock assistants worked with local citizens to review energy bills (electricity, heating fuel, and vehicle fuel) for all municipal operations (buildings, vehicle fleets, and street lighting) for one year, typically 2005. The data they collected included the cost of energy, as well as the number of units of energy used (gallons of fuel or kWh of electricity). This information was analyzed using the ICLEI (Local Governments for Sustainability) Clean Air and Climate Protection software tool and the online Portfolio Manager software from the Environmental Protection Agency. Each participating municipality was provided with a report that described the relative amounts of energy use, greenhouse gas emissions, and energy costs of the municipal sectors as well as each individual municipal building. Each report gave specific recommendations about the priority actions the municipality can take to save energy costs.

Challenges experienced in the baseline inventory projects in 20 Monadnock municipalities were very informative to other inventory projects across the state. The Cool Monadnock team learned the critical need to gain the buy-in of local citizens, staff and officials who needed to really grasp the fiscal and strategic advantages of planned energy conservation. Another important challenge was dealing with the varied forms of billing from energy providers as well as record keeping within municipalities. In fact, experiences within the Monadnock region contributed to state-wide discussions with utility companies about stream-lining on-line access to energy data and possible mechanisms for moving municipal energy data directly into software tools.

The Cool Monadnock team completed baseline inventories for the following towns:

Alstead

Chesterfield

Dublin

Fitzwilliam

Hancock

Harrisville

Marlborough

Nelson

Peterborough

Richmond

Rindge

Sullivan

Surry

Swanzey

Temple

Appendix B: Sample Town Report

Municipal Greenhouse Gas and Energy Use Baseline Report for Temple

Municipal Greenhouse Gas and Energy Use Baseline Report for Temple

This report is a summary of greenhouse gas emissions and energy use for the town of Temple, NH for the year 2005. The focus of this report is the municipal operations of the town, with special emphasis on town-owned buildings. It does not encompass residential, commercial, or industrial energy use. It has been prepared by the Cool Monadnock Project,[1] a collaborative project of Clean Air-Cool Planet, Antioch New England Institute, and the Southwest Regional Planning Commission. Data was gathered through the volunteer efforts of the Cool Monadnock Town Representative and analyzed by the Cool Monadnock team, using EPA Portfolio Manager software and Clean Air and Climate Protection software provided by ICLEI.[2]

Town population: 1,554 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2006)

Area of Municipality: 22.5 sq. mi.

Population Density: 69.8/sq. mi.

Number of municipal buildings: 4.

Total area of municipal building space: 10,108 sq. ft.

Average energy intensity of all municipal buildings: 43 kBtu/sq. ft.

Number of street lights: 1 (library, town hall parking lot)

Number of vehicles in fleet: 13

Number of municipal employees: 10

Total cost of municipal energy use in 2005: $31,991

Total municipal energy use in 2005: 2,163 MMBtu

Total municipal CO2 emissions in 2005: 159 tons

[2] For more information on EPA Portfolio Manager Software, see www.energystar.gov/index.cfm?c=evaluate_performance.bus_portfoliomanager. Information on CACP software is at www.cacpsoftware.org.

Municipal Sector Analysis

For each participating municipality, data was gathered on the operations of several sectors under the jurisdiction of the municipal government: the buildings, vehicle fleet, employee travel (how much municipal employees travel to work and other travel for municipal business), street lights, water and sewage, and waste. Different types of energy use were considered depending on the sectors, such as electricity use, heating fuel use, fuel for vehicles, and tons of waste. Where records were available, the costs of purchasing these energy sources were factored in to the analysis. The ICLEI software was used for the analysis of the aggregate data on all municipal sectors.

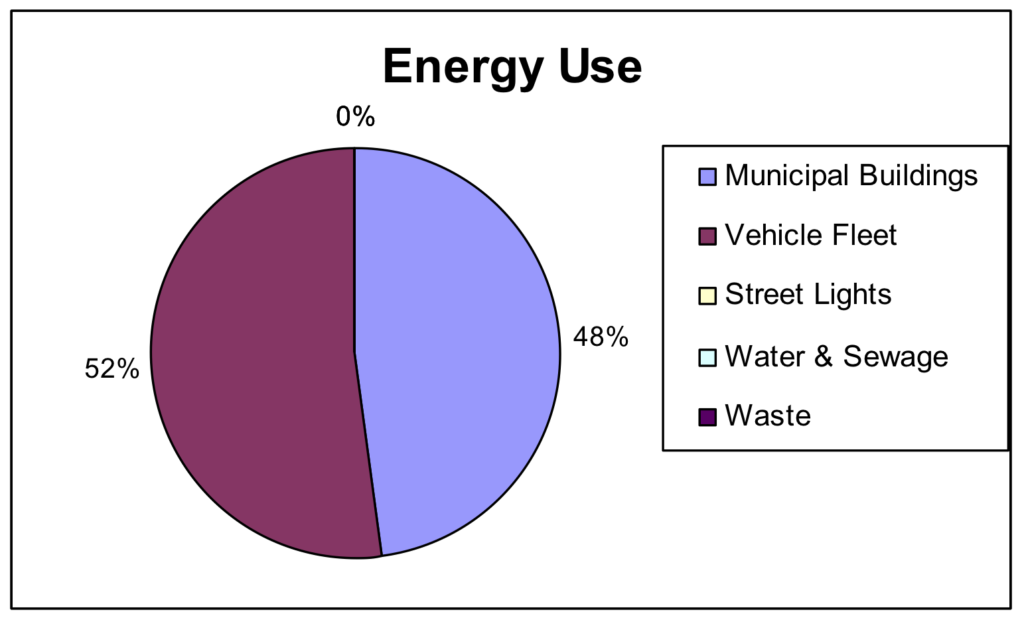

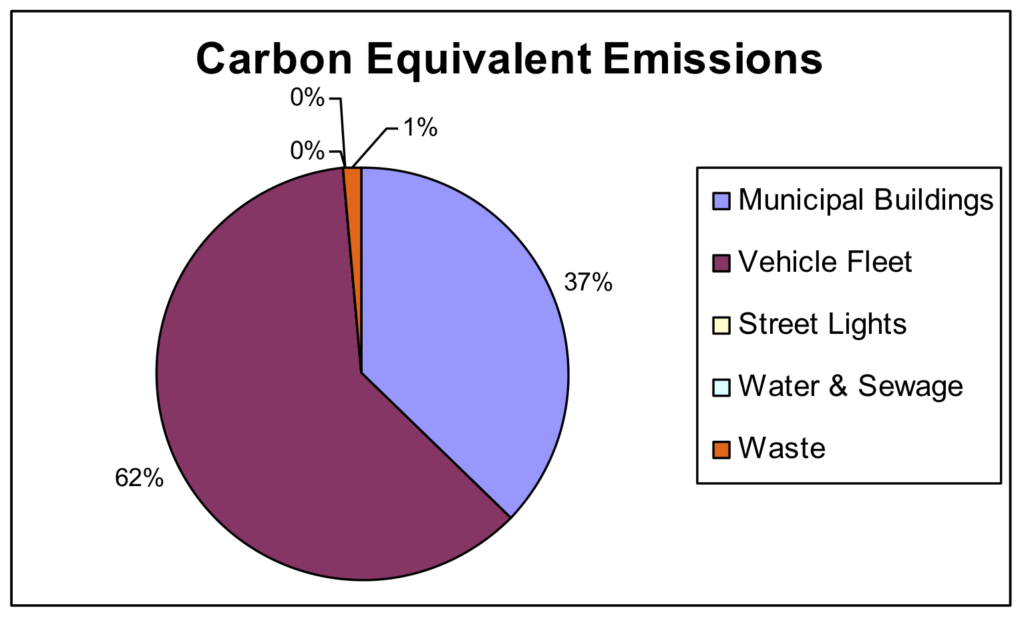

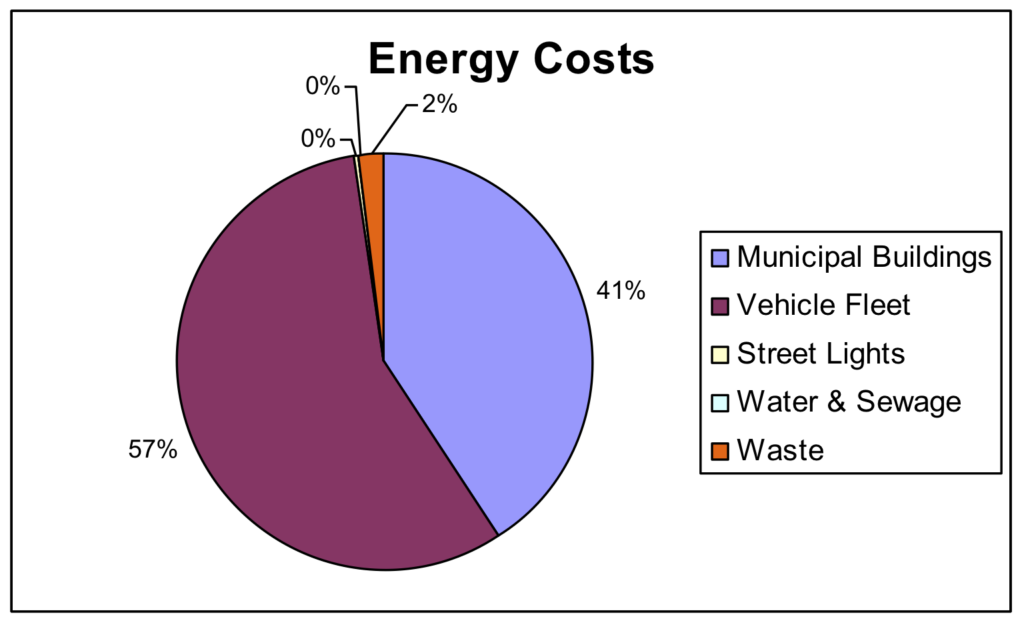

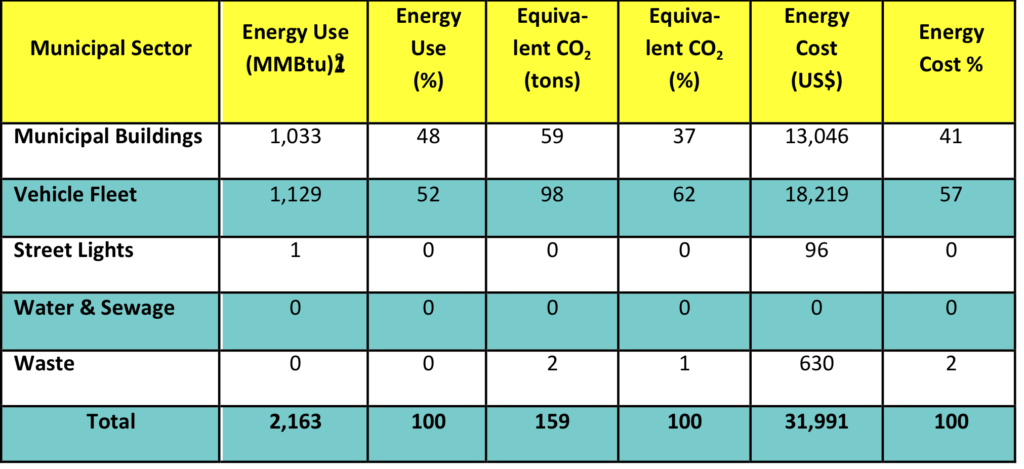

Table 1. Energy use, equivalent carbon emissions[2], and costs, by municipal sector (Source: Cool Monadnock inventory, 2008 Generated by CACP Software)

Table 1. Energy use, equivalent carbon emissions[2], and costs, by municipal sector (Source: Cool Monadnock inventory, 2008 Generated by CACP Software)

[1] The Clean Air and Climate Protection software presents energy use in MMBtus, which is one million British Thermal Units, a common measure of energy consumption (see www.energyvortex.com/energydictionary/british_thermal_unit_(btu)_mbtu_mmbtu.html).

[2] According to the Clean Air and Climate Protection software, “Equivalent CO2 (eCO2) is a common unit that allows emissions of greenhouse gases of different strengths to be added together. For carbon dioxide itself, emissions in tons of CO2 and tons of eCO2 are the same thing, whereas for nitrous oxide, an example of a stronger greenhouse gas, one ton of emissions is equal to 310 tons eCO2.”

Snapshot of 2005 Municipal Energy Use, Emissions, and Costs by Sector

Graph 1a. Municipal Energy Use (MMBtu)

Graph 1b. Municipal Carbon Equivalent Emissions (tons)

Graph 1c. Energy Costs by Municipal Sector ($)

The three graphs illustrate the fact that the vehicle sector is the most significant sector in Temple in terms of energy use and energy cost, and especially in terms of carbon equivalent emissions. The vehicle sector comprised 52% of energy use and 57% of energy costs, but a full 62% of emissions. The building sector is the only other significant energy sector in Temple, using 48% of the energy and comprising 41% of the energy costs, as well as contributing 37% of the carbon equivalent emissions. While the waste sector does not generally contribute to energy use in towns, it did register as 1% of the town’s emissions and 2% of its energy costs. In Temple, the town’s four buildings and thirteen vehicles offer the greatest opportunities for energy savings. The Cool Monadnock project performed specific analysis on municipal buildings that is outlined in the following section. This information should be helpful in identifying which buildings within the building sector present the greatest opportunities for savings.

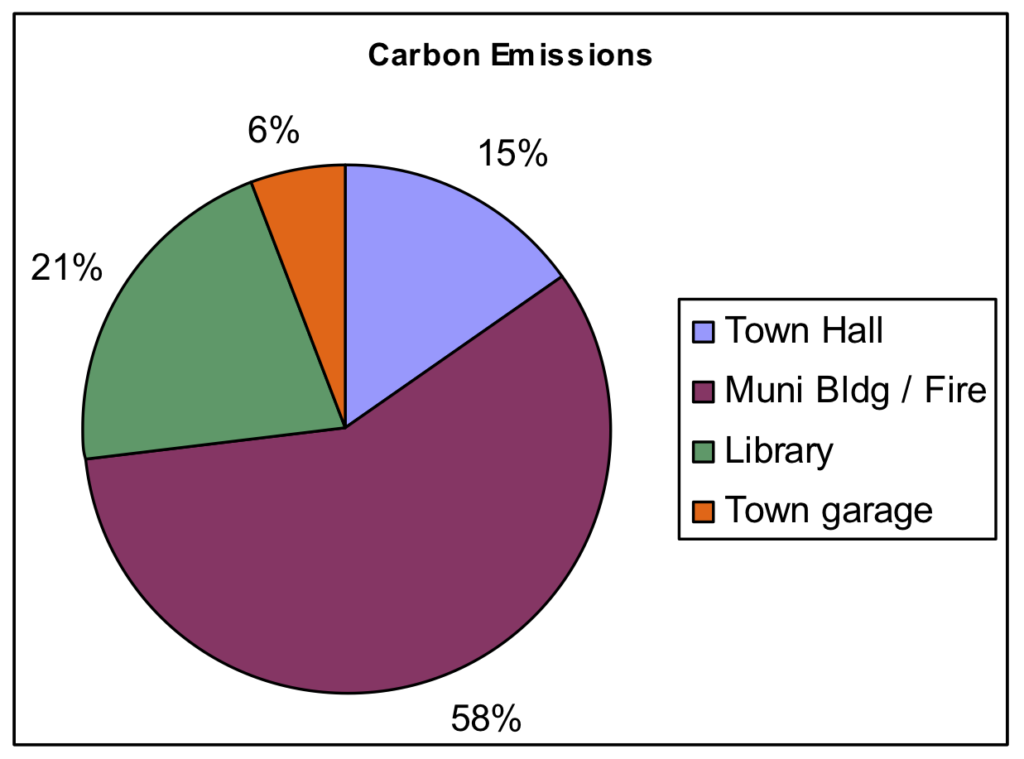

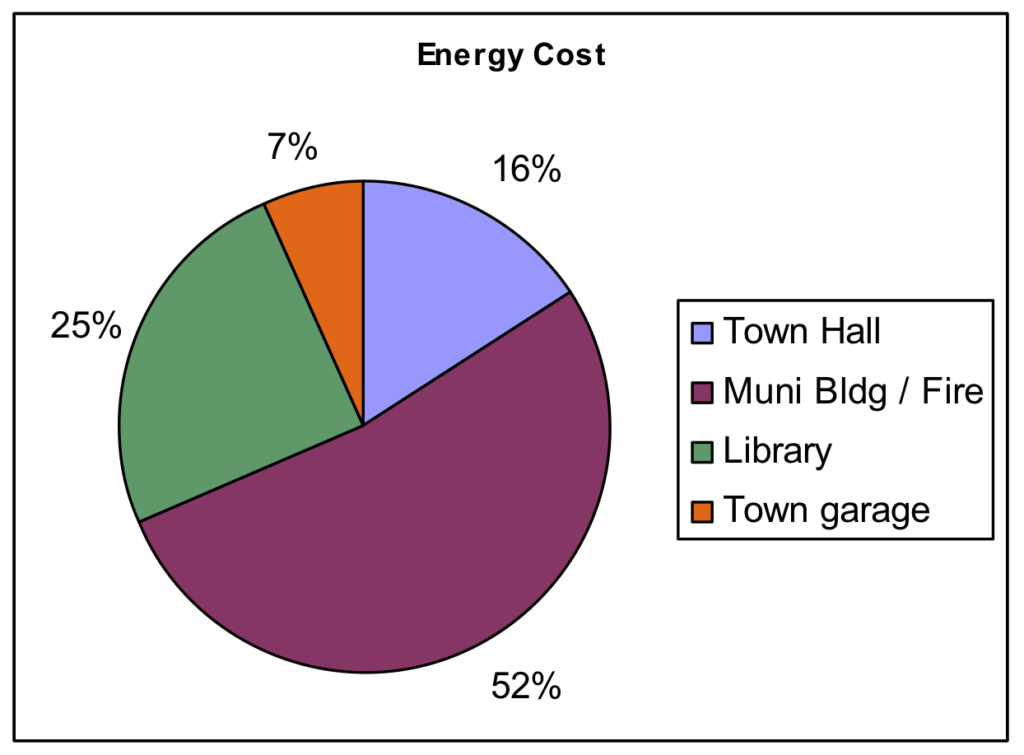

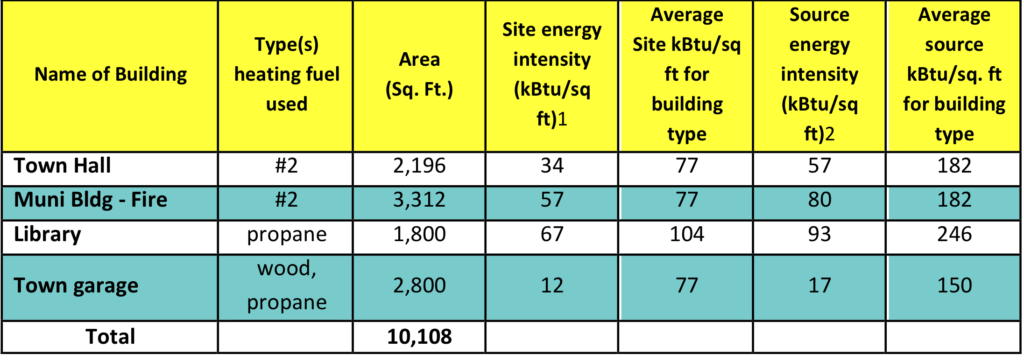

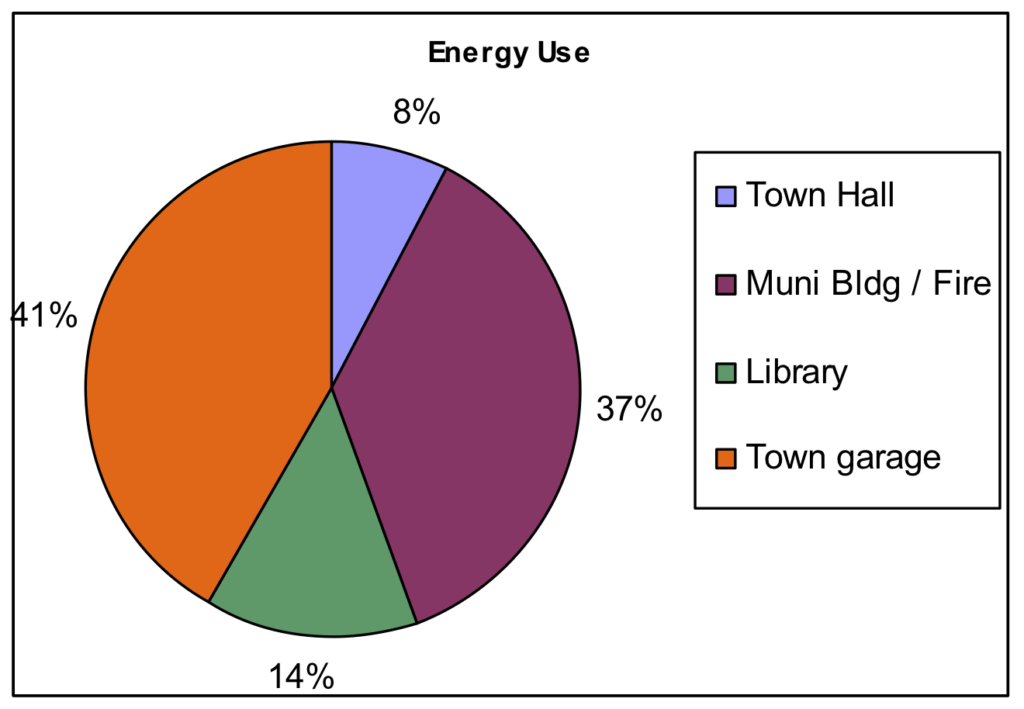

Building Performance: Energy Use, Emissions, Costs

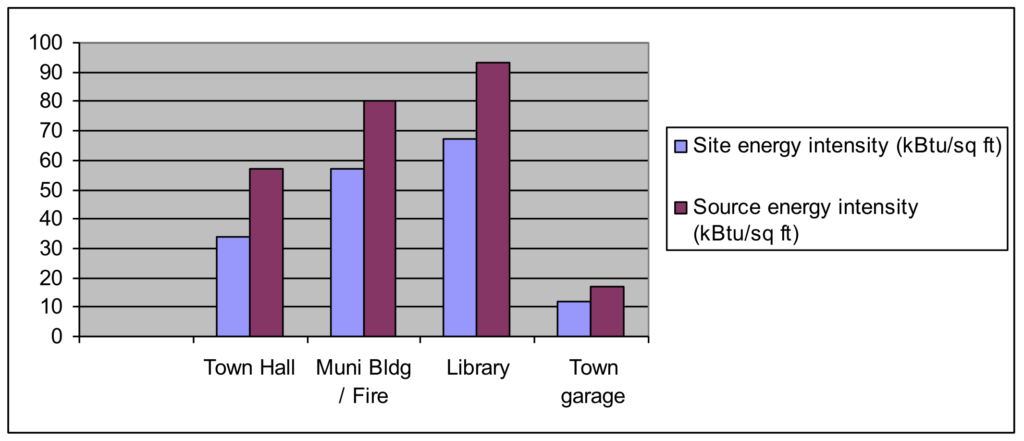

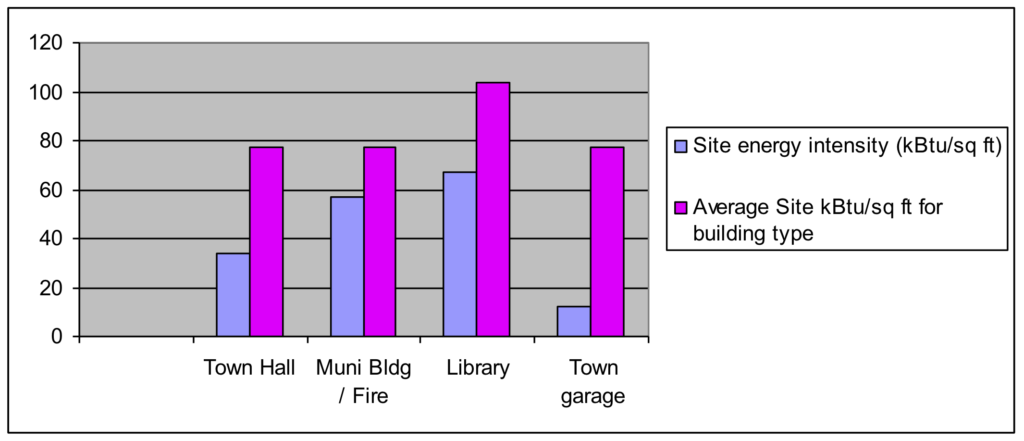

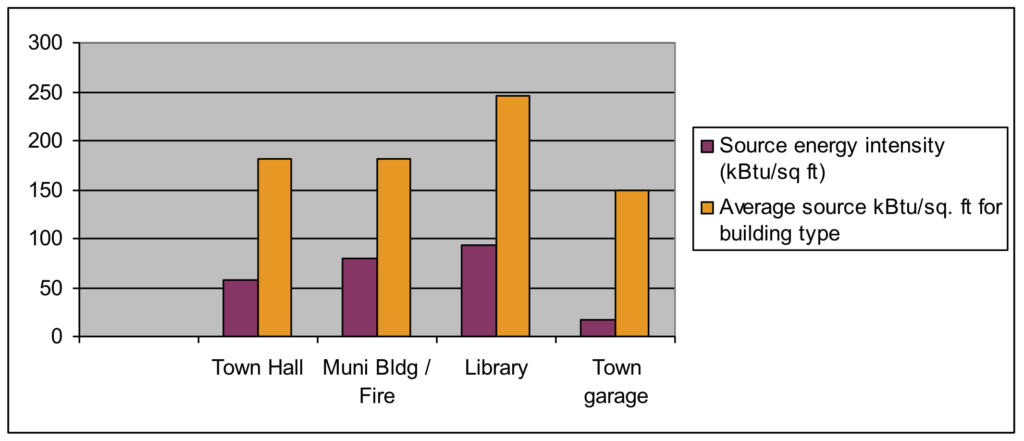

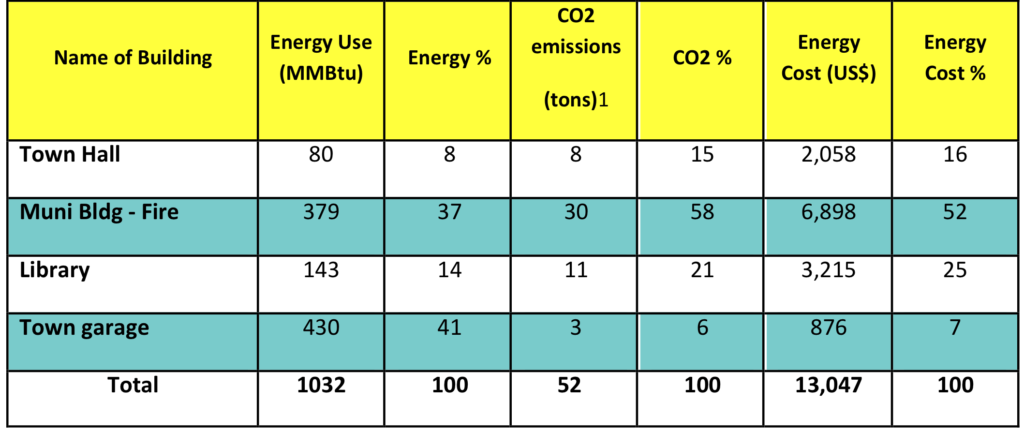

Data was gathered for each individual building managed by the municipality. The following table combines data from EPA Portfolio Manager software (energy intensity, CO2 emissions) and CACP software (energy use). Data on costs were entered into the Portfolio Manager software. Graphs below illustrate the relative intensity of energy use and their costs among the buildings under the municipal jurisdiction.

Table 2. Carbon emissions, energy use, and costs, by municipal building (Source: Cool Monadnock inventory, 2008, Carbon data generated by EPA Portfolio Manager Program; energy use generated by CACP software)

1 – Carbon emissions on the EPA Portfolio Manager software are measured as carbon dioxide emissions only and do not include equivalents for other types of greenhouse gas emissions.